Last weekend I attended the opening of 'He Toi Reikorangi: Te Ātiawa artists celebrate Matariki' at Mahara Gallery in Waikanae, on the Kapiti Coast of the Wellington region (New Zealand). It was super exciting and hundrends of people showed up to celebrate and show their support for the exhibition, including some of the best Māori artists in the world. For the duration of the opening weekend, Mahara Gallery invited myself, Rangi Kipa and Mitchell Hughes to showcase our tā moko expertise.

The fact that this exhibition opening was in Waikanae was personally significant to me, because my grandmother spent a lot of her life growing up in Waikanae, and her grandfather Wi Parata was a well known leader of the area and one of the biggest landowners - in fact Waikanae was once known as 'Parata Town'.

Iwi exhibitions are one of my favorite types of exhibitions because they reinforce and strengthen the whakapapa/genealogical bonds between the artists and the people of the iwi they belong to. Iwi exhibitions are a positive and uplifting community kaupapa that bring people together, showcasing the artistic excellence and skills amongst that particular tribe - I think that in itself, is an inspiring and empowering outcome.

A section of the moko peha that I worked on at Mahara Gallery during the exhibition opening weekend.

My eight year old apprentice, Ria Te Uira, stretching skin at Mahara Gallery.

My niece Ria Te Uira is a great little apprentice.

One of the reasons that I love to bring tā moko into art galleries is that it exposes and opens up the art form and cultural practice, to an entirely different audience, an audience that may not ever have the chance to see tā moko happening in real life, in any other situation. The potential for engagement with the public is great in an art gallery setting, and I enjoy answering the many and varied questions that people come up with. Having tā moko artists working in an art gallery space is magnetic, cutting edge, and a rare opportunity for gallery viewers to witness the tā moko process.

Another reason that I enjoy bringing tā moko into art gallery (and museum) settings is because I believe that all of our Māori art forms are inter-related and connected. Our various different art forms are at their strongest when put together and combined, contrasted against each other, complimenting one another, feeding into, informing and in conversation with one another. A decorated wharenui is a prime example of this, as is kapa haka where you see many of our art forms in relationship together at once.

The idea of inter-related art forms is part of the reason why I love collaborating and working alongside other artists, that use different mediums to me. It is also why I am currently enjoying the use of taonga puoro by Jerome Kavanagh, to compliment my tā moko process.

Tohunga tā moko, Rangi Kipa was also tattooing at Mahara Gallery for the exhibition opening weekend, as was moko artist Mitchell Hughes.

An outstanding modern work by master artist, Rangi Kipa.

Inspiring tukutuku work in the exhibition by my whanaunga, expert weaver Kohai Grace.

Photographic portraits in the exhibition featuring Te Ātiawa women and their moko kauae, by Heloise Bergman.

Whakairo in the exhibition by my whanaunga, Rakairoa Hori.

Painting in the exhibition by one of my favorite contemporary Māori painters, Darcy Nicholas.

Outstanding hue by expert weaver, Veranoa Hetet.

I love this work by Tracey Morgan using seaweed and tāniko.

I have two prints on show in the exhibition, 'Manu Ariki' and 'Hine Ariki'. The kete shown in the foreground are by Snooks Forster.

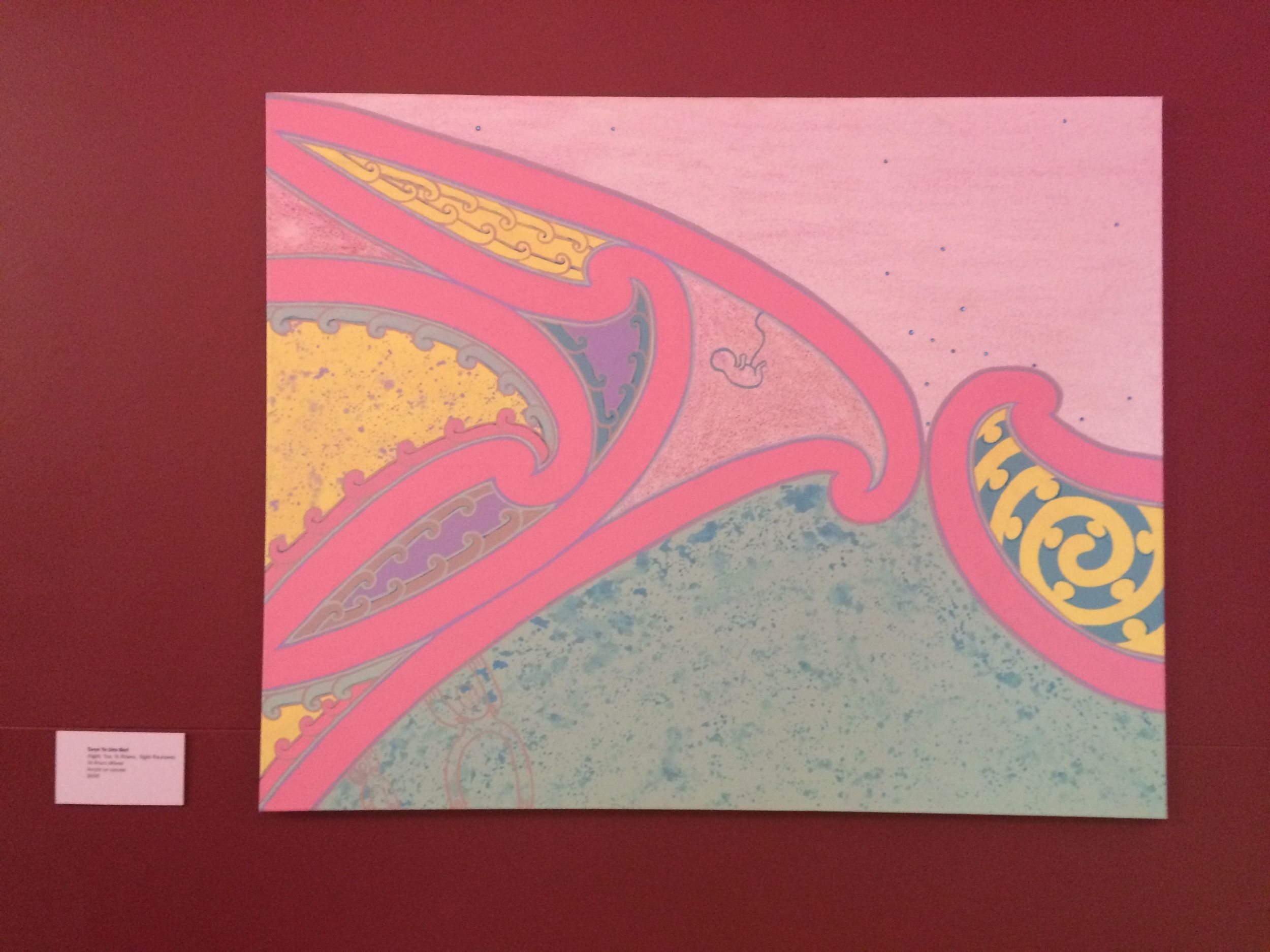

My painting 'Te Āhuru Mōwai' currently at Mahara Gallery. This painting refers to a 'cosy haven' inside the womb of a woman, the home of a baby growing, the amniotic fluid and the dna / ancestral material that makes up the baby and who the baby is / will become.

The photos of art work shown in this article are just a snapshot of the full exhibition and there are many more awesome and innovative works on show until 12th July 2015, so go and see for yourself!