Many thanks to all of the beautiful people, men and women who came to get tattooed by me this year!

May we all have a wonderful and blessed 2021 together!

Ngaa mihi nui!

Wahine Toa

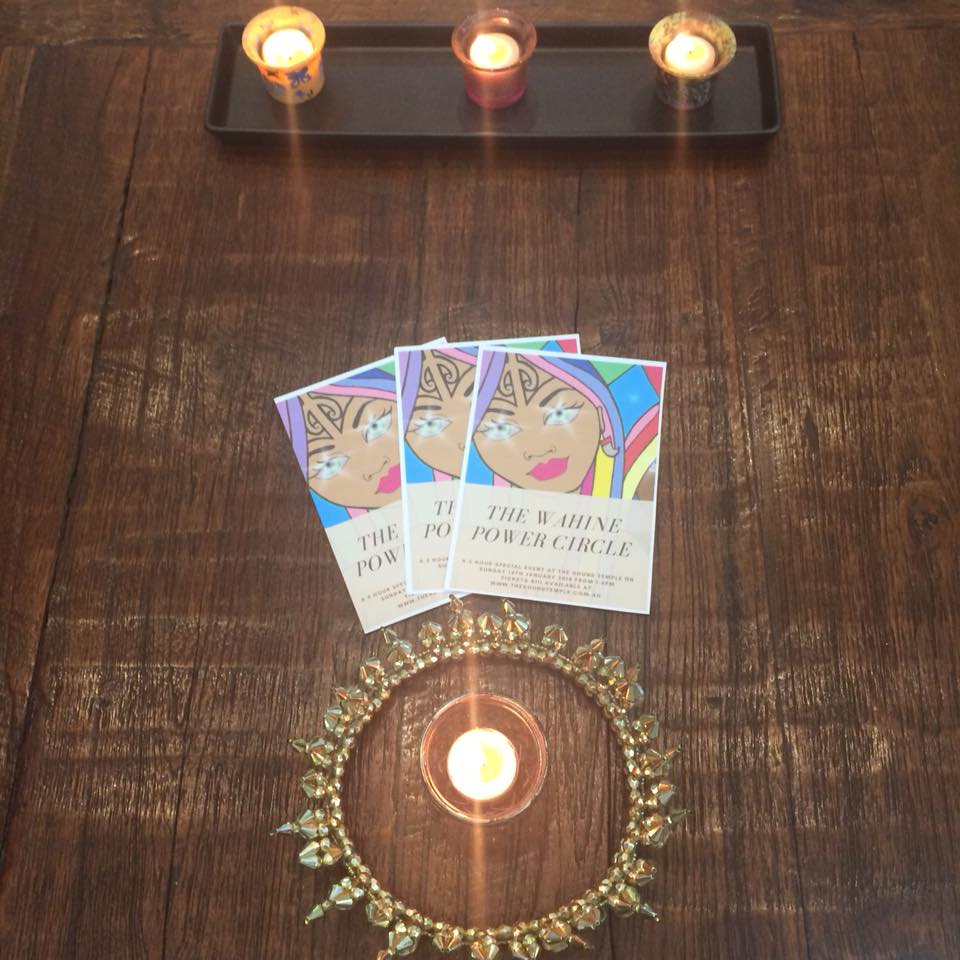

The second 'Wāhine Power Circle' special event in Perth, Western Australia

Last Sunday I ran the second 'Wāhine Power Circle' event at The Sound Temple in Perth, Western Australia, with invited co-facilitators Sofia Tuala and Jerome Kavanagh.

It was a fabulous day and some great connections were made.

There were tears, breakthroughs, laughter, letting go of the old, singing, calling in the new, sisterhood, empowerment, snacks, herbal teas, sound healing, guided affirmations and so much more!

THANK YOU TO ALL THE AMAZING WOMEN WHO ATTENDED!

Sold out art prints: wahine toa limited edition of 45

I am very pleased that these limited edition art prints have now all sold out! Big thank you to everyone that purchased one, I really value your support!

Mauriora!

Taryn

"A māreikura, an angel, a protector, an icon, a higher self, a vision, a messenger being, a friend, a reflection, a woman of light and strength, a reminder, a role model, an alter ego, a sister, a mother, a daughter, a grandmother, a guardian, an aunty, an archetype to aspire to be like, a modern day warrior, a personification of the divine feminine - this is what the 'Wahine Toa' art print speaks to and represents."

Sold out art prints! Thanks to you guys!

Thank you to everyone that has been purchasing my art prints so far, I really appreciate your support and I love the idea of my art going all around the world and into peoples homes and personal lives. Ngā mihi ki a koutou katoa!

These 'Te Waipounamu' prints were a limited edition run of 10 and they are now all sold out.

Progress shot of 'Te Waipounamu' A3 drawing.

Progress shot of 'Te Waipounamu' A3 drawing.

My 'Ūkaipō' pink art prints as shown below were a limited edition run of 20 and they are now all sold out too.

$10NZD from every one of these art prints was donated to Kai4Kids, a New Zealand charity that provides food to schools in low decile areas. Together we donated $200NZD to this great kaupapa - thank you, thank you, thank you.

My latest art print to sell out was an A4 limited edition run of 20 again, called 'Of course i'm a feminist' as shown below. Thanks to everyone that bought one!

I am currently working on some more new limited edition art print designs (they are so much fun) so keep an eye out! Thanks again for buying my art, I am so grateful!

Moko peha by Julie Paama-Pengelly, photographed by Norm Heke of Te Papa Tongarewa National Museum of New Zealand.

'Moko artists speak' an interview series by Taryn Beri: Interview #1 Julie Paama-Pengelly

I was inspired to create this new interview series speaking to different moko artists from different backgrounds, of all ages, from all around the motu, because I was interested and curious to know what other artists and cultural practitioners had to say about certain matters. I also wanted to provide a platform, a forum and a space for their voices to be heard, their stories to be told, and their lessons to be taught - on an international, easily accessible scale (i.e. the internet). Too often I see people overseas speaking for us, over the top of us and on matters that concern us and our culture, and I think it's time for more Māori to speak up for ourselves on an international scale.

Following the huge response to my article about the difference between kirituhi and moko, I became more acutely aware of the many and varied different opinions, perspectives and points of view out there regarding tā moko, and I wanted to know more about what other moko artists had to say.

I always enjoy hearing the personal story behind the journey of an artist and their work, learning about the ups and downs that make a career in the arts - and I thought my readers might also be interested in this. I hope that these interviews will educate, inspire and enlighten.

The first interview in this interview series, is with Julie Paama-Pengelly, a woman who in my view has been one of the pioneering female moko artists of Aotearoa, in modern times. Before I became involved with tā moko and I was working as a Māori Fashion Designer in my own business, and as a Māori Graphic Design Associate (for a Māori Mental Health Organisation) in Wellington (around 2007), the only female moko artists I had heard of back then, were Julie Paama-Pengelly and Christine Harvey. That's not to say that there weren't others out there, it's just that I was not aware of them at that time. Nowadays, there are around 10-15 Māori female moko artists that I know of (I hope to interview more of them in this series) and no doubt more and more sprouting up every day - I think it is great for the art form and for our people to have a wide range of artists, personalities and styles to choose from and I find it really inspiring and interesting seeing what other artists are doing and where they are taking their own individual tā moko practices.

With no further ado, here is the interview and Julie Paama-Pengelly's answers to my questions! The views and opinions expressed in all of the interviews in this series, belong to the person being interviewed (obviously) and are not necessarily the same as mine (the interviewer) but hey that's what makes it interesting food for thought!

Moko peha by Julie Paama-Pengelly, photographed by Norm Heke of Te Papa Tongarewa National Museum of New Zealand.

Name: Julie Paama-Pengelly, age 50 years young

Iwi affiliations: Ngaiterangi, Tauranga Moana

Where are you based: Mt Maunganui at the base of my maunga Mauao

A note to the reader by Julie Paama-Pengelly:

My views are only possibly mine alone and they are ONE perspective that is in a constant state of change and revision. The important thing for me is that I am prepared (and this includes knowing what I don’t know!) to modify the way I think and feel about our culture as it evolves and either reclaims health or looses its footing because as with anything, it is in a constant state of change. I think it is dangerous to claim there to be one way for Māori to behave or be as this may exclude other Māori. It is however important, when involved with tā moko to challenge the integrity of someone to receive moko from you as in the end it is both your integrity and that of the art form that stands to be compromised.

How did you get into tā moko?

I trained as a secondary teacher in 1991 and was inspired by Robert Jahnke and Derek Lardelli at a Māori Art teachers wananga that I attended. I went on teaching section to Gisborne and witnessed Derek Lardelli applying pūhoro to Piri Sciascia and this led me to study Robert Jahnkes art papers extramurally (off-campus) while I taught art to Māori students at Lytton High School for two years.

Who mentored you, if anyone?

Kura Te Waru Rewiri, Shane Cotton and Robert Jahnke in principles of Māori Design. Kura Te Waru Rewiri – Mana Wahine! Most people attribute my mentorship in tā moko to Rangi Kipa however I already had my design knowledge and Rangi and I started our formal moko learning at the same time – most knowledge I gained on my own and by osmosis – watching a variety of artists work and working it out myself – practice practice. The advantage of doing it this way is that I freely explored a range of influences.

Did you have any formal education that helped you on your journey and if so please tell us about it?

Degree in Social Sciences (Anthropology) which gave me the historical foundation of searching for cultural clues amongst our old objects and social behaviours and helped me to understand our cultural history through an understanding of everyday life which art made sense of. Te Reo Māori was part of this.

Diploma in Secondary Teaching – Art, which had a strong Māori arts focus at the time that I undertook my studies and I had heaps of exposure to Māori Art and Design on this programme through teacher in-service trainings and the resources available at schools.

Masters in Third World Development – enriched the connections between Pacific Cultures Art and Design practices and the importance of these to Māori development.

Ataarangi – powerful medium for learning the reo and through the reo accessing our world of knowledge

Bachelor of Māori Visual Arts (Honours) – amazing teachers, huge focus on research, read every book and studied every Māori artist as well as every single object in every museum. This programme taught me the power of research and exploration of my own artistic expression.

Masters of Māori Visual Arts (Honours) – expanded all of the above in a powerful way and brought all my learnings together.

Moko kauae by Julie Paama-Pengelly.

How long have you been doing moko for?

For at least twenty years but probably more as each year now I forget to count. For a great deal of this however I was teaching, raising a family, studying, engaged in health promotion and working on committees – I didn’t have the luxury of simply being a moko artist.

What/who inspired you to be a moko artist?

I guess the one person would be Derek Lardelli as it was my experiences around Derek that made me resolute to be involved with moko - but I was hugely influenced by a range of artists, and their experiences, for example Ralph Hotere has been influential.

Why do you choose to be a moko artist? What is the best thing to you about being a moko artist?

All my learnings have been about enriching Māori cultural health and at the same time art practice and it became obvious to me right from the moment that I saw Piri receiving his moko from Derek, that powerful role models wearing this taonga could have a commanding influence on the mana of Māori people and things and be an agent for instilling our people with their world again. I always believed in transformative change and wanted to spend my life doing something meaningful. When I finished University I wanted to volunteer in the Third World, to help the poor, then I realized that the important messages from my journey was that Māori were deprived in so may ways and cultural loss was at its heart. Doing tā moko felt like a way that I could work on this while still learning from within my own culture and do what I had always loved – art.

What artists do you look up to/admire? Why? Who are your role models when it comes to tā moko? Why?

Ralph Hotere – for his understandings of Te Kore, Te Pō and Te Ao Mārama in there most powerful realisations and his understanding of simplicity of balance of form and space. For the heart he brings to his work.

Kura Te Waru Rewiri – for her mana wahine principles and her formal skills in design and form and her absolute humility, beauty and talent while often overlooked in the art world in favour of male artists.

Shane Cotton – for his approach to new visual language and absolute skill at bringing beauty to paint and to contemporary Māori painting.

Robert Jahnke – for his contribution to research and his discipline in finding every bit of knowledge. For his emphasis on excellence.

Derek Lardelli - for his passion for mātauranga a moko and driving this through Toihoukura, which helped the art of tā moko grow with the knowledge to support it.

Rangi Kipa – for a solid language of carving and a willingness to create new modern Māori design languages and for his belief in a good line and integrity of design first.

I am largely impressed by much of the work being done by moko artists throughout the motu – there is so much talent and variety. I tend towards the feminine aesthetic which I believe there is a distinction and some of the large male designs are not so appealing.

Describe your ideal client for us?

Well this depends I guess on what type of moko however, readiness to cope with the pain is important and also being prepared to entrust the moko artist with their kaupapa. I exhibit a lot of patience with a client and am willing to spend time with them but I feel disrespected if they don’t put time into their preparation and give equally to the relationship. My ideal client is NOT one that brings a design drawn by someone else! But I do have a great enjoyment of coverups because making a difference is often rewarding. In some ways I don’t have an ideal as I feel part of my responsibility is to be able to collaborate with everyone and enjoy the people that we are – life is about people and they have the biggest lessons.

Julie Paama-Pengelly tattooing, photographed by Norm Heke of Te Papa Tongarewa National Museum of New Zealand.

What do you want to do more of in your moko practice?

Explore advanced kōwhaiwhai and alternative design languages, some of our more complex designs. I like working every piece as extremely different as possible and I try to beat the recognition of each piece being associated with me. I like experimenting but I am really rigid with my positive and negative balance and I try not to compromise this but look for new ways in which to enhance the form of the body. More exploration of old practices, old pattern making and old techniques.

What do you want to do less of in your moko practice?

Shading is less appealing to me if it is associated with figures, such as carved figures as for me it starts to look like drawing instead of moko. The simple balance of positive and negative should remain as uninterrupted as possible. I am less keen on colour but when I do use it, I try to experiment as well. I prefer the blacks of our tradition.

What are the most important qualities for a moko artist to have, in your eyes?

Absolute integrity in their relationship with clients – this can't be stressed enough and to have humility – I detest a rock-star mentality and believe that to do tā moko is to serve, not to impose arrogance onto people. To be continually learning and evolving and to respect the art form by being in good mental and physical health. As a female artist you need to have a certain boldness to move ahead even when you are challenged and hurt by men, and other women. This is the only way I survived in the past because often the hits would come from both sides – we as Māori can be very destructive of each other. To not belittle the achievements of fellow female tā moko artists as they have had their own battles and in the end your work will speak for you – you are expected to keep working hard at it!! I believe in sisterhood and respecting this, wāhine should not seek to undermine each other in anything, especially for the attentions of men as this just takes us from where the real battles lie.

What are you goals, dreams and aspirations for your moko practice over the next ten years?

Ha! That I can still see and my hands still move!! To be doing at least the same level of tā moko work that I am doing now but I would like to have more time to spend painting! To celebrate everything that it has become through the work of others and to share what I know. In the beginning there was a great deal of male energy invested in tā moko and this had an impact on the type of moko that wāhine sought as they were often the humble ones deferring to their whānau. Often Māori men would make decisions with regards to what moko merited attention and what didn't. My personal goals for moko are not so much what I want but what I feel a responsibility to as a person that is exposed to the widest range of perceptions around tā moko and also with some view to the secret shames and pains that clients share with me. For these reasons I support the imperative that the kaitā wāhine have all expressed, that the moko kauae requires our urgent attention so that we may bring forth and support the mana and wellbeing of our wāhine. I would feel satisfied if, in ten years, we see moko kauae as the norm rather than the exception.

What advice would you give to any aspiring moko artists out there?

Do not be lazy – you must keep learning and absolutely, understand and be able to draw the major design principles – be disciplined, practice hard and DO NOT tattoo skin if you do not have these understandings and skills. Seek an apprenticeship or learning institution and be the very best student that you can be. Be prepared to sacrifice to be the best and respect that your teacher has likely invested a great deal of their life putting in work to get to this point – respect them (even if they have flaws) at all times as you will expect clients to respect you. The first lesson – all tā moko is about respect.

Do not ‘steal’ other cultural art forms because you can't be bothered doing your homework on our own. Māori art is unique and extremely complex and I think that currently artists are only utilizing around 10% of our actual kōwhaiwhai language – we need to keep bringing our own knowledge to the fore and not replicating others (unless of course we are establishing our whakapapa relationships to old art languages).

Importantly – clean up your act. Be a good role model for the respect that you expect – smoking, drinking, drugs – should not compromise your client practices and personal hygiene is important as are good manners and language!

What other art mediums do you practice, if any? What do you love about the other art forms that you practice? How do they relate to your moko work?

Graphic design (computer assisted) and drawing usually using my Māori design skills – it's great as usually it's giving a Māori identity to something that can have a widespread audience as a powerful identity.

Curatorial (exhibition design) based on my knowledge of contemporary Māori and Pacific Art – I love creating Māori meaning in space and allowing our creative voices to have expression to the world. Supporting other artists is important to me.

Printmaking – I love playing with Māori design and old imagery to reimagine a powerful modern Māori identity – turning historical images into positive Māori identity.

Painting – my favourite medium as I paint in abstract. This is emotional to me, my relationship with paint and its expression but I also use painting to engage discussion about the issues and adaptations our culture is continually being forced to confront.

The artist Julie Paama-Pengelly, photographed by Logan Davey.

Have you worked overseas much? If so, where? What are the best things to you about working overseas? What are the worst things to you about working overseas?

Yes, I have enjoyed a tā moko residency in Santa Fe and with fellow indigenous tattoo artists. I haven’t really enjoyed conventions unless there is indigenous support there. I enjoy residencies as they usually enable a more cultural context, speaking and interacting with other communities and cultures. The BEST thing about international travel is sharing the tatau revival with other indigenous communities and feeling humbled by their own stories. I miss home and my kids and I don’t like to travel without them, they are my rock.

Do you prefer to work privately or in tattoo studios? Why/explain?

I have enjoyed working on marae and traveling a lot with moko in the past however through the years with a family I have learned that it is healthier to separate family and work – my kids deserve my attention and they require more attention to their own interests as they get older. I love travelling to marae and personal homes and tā moko has taken me all over the country. This however can be incredibly tiring, lack of sleep, often a lot of gear preparation and bad lighting etc – and too much good food! I never thought I would enjoy working from a studio but I do as I can separate my professional space and have privacy when I wish. It also encourages the clients to treat me in a more professional manner and allows me to rest and control the work environment in fact it is crucial that the artist can put their comfort first to ensure the best artistic result.

How do you feel about non-Māori tattooers, incorporating Māori design and patterns into their art or tattoo work? Do you approve/disapprove? Why/explain?

I’m really not fond of how Polynesian artists are using a large kōwhaiwhai element to break up areas of pattern in their work – it is usually not harmonious, nor correct and to me it doesn’t work with their geometric languages. There are a small handful of artists that are doing a better job of it but I don’t think it adds to the integrity of their own art forms. I think they should spend time exploring new pattern languages and compositions without using Māori design. Essentially without having to waffle on, I disapprove as it generally doesn’t add anything to our art form and often reinforces less-flattering design.

Do you tattoo non-Māori people and if so, why/why not? Do you differentiate between what you do for non-Māori clients compared to what you do for Māori clients? If so, how do you differentiate and what is the difference, if any, in your eyes, between the two?

In the early days, I refused to tattoo Pākehā unless they had an intimate connection with Māori through family etc. this was because I felt that Māori had to see their art form in a healthy place before non-Māori could be seen to ‘steal’ this. However, today, and operating out of a studio, I am willing to tattoo non-Māori. It is always constituted from my tā moko vocabulary but the form and detail knowledge may be missing – it may be small elements of design in a fern or spiral etc if it is something for say, a tourist. Why? Because there is great power in ensuring non-Māori come along for the journey and are educated so they don’t go to a non-Māori and ask for our art. If it comes from me, it's moko and I give clients the same respect. For Pākehā that are more involved with respect for our things, I will give more substantial moko. My role is to progress our art form and not belittle it or the people that I apply it to. I see applying moko on non-Māori as a powerful tool towards our cause – we can ensure people have a bigger Māori heart and work for our us – we can't advance without friends and our whakapapa extends beyond ourselves, just as our world now extends beyond our initial beliefs and limitations.

Do you use/support the term ‘kirituhi’? If so, why? If not, why?

No, for me moko is moko, the language lies with the artist and if I apply it to anyone, its moko. If its applied by non-Māori its not moko but an appropriation of it. I think labeling it as kirituhi is a little degrading to the wearer and also to you as an artist. I mean we put our design on T Shirts – its really down to the mana of any wearer to wear something well, Māori or Pākehā and as an artist, you are applying the best version of moko no matter the kaupapa.

What do you find challenging about being a moko artist? Have you had any challenges on your path as a moko artist? What were they and how did you overcome them?

Plenty – it’s all a challenge, everyday. These are okay as long as you don’t lose faith in your ability to overcome them. Religious views and colonized ideas, while I respect people and their rights to these views, they limit our ability to see the threats to our culture. At times they swallowed me however, surrounding yourself with a few good friends that absolutely support you and supporting others will help you move through. Realize that people that want to hold you back or put you down are power tripping, protecting or hiding something themselves.

What do you want to contribute to the art form in you career as a moko artist?

Shit, I don’t know how to answer that one …? Sometimes things just sort of come to you as what you want to do, not because you think of it yourself either, someone else tells you that you should do it. That’s why I’m doing a book project, because I got blocked from one once for defending the rights of my client and also because I think we spend too much time trying to define what ‘authentic moko’ or anything else looks like.

I want to offer my perspective, not because I am an authority but because I realize that I have history to bring to this perspective, one in which moko was rare and being rebirthed – to where we are today, a hugely persuasive art form, internationally. I want to re-establish the importance of the individual artist – even historically – in the creative process – we were never passive inheritors of design, but always artists.

To connect with Julie online, go here.